Greg Tate Day Is Not Just a Tribute. It’s a Civic Act.

Celebrating a Visionary to Reignite Our Own Responsibility

Co-published with Civics Is Sexy

I first met Greg Tate on 14th Street, in Union Square Park, New York City, in the summer of 1993, right after a triple bill that echoes strong in my memory. His band Women In Love, with the inimitable Helga Davis, had just shared the stage with Blueprint (featuring Marque Gilmore on Chapman Stick, David Gilmore on guitar, Mikel Banks and Yvonne Heavlow on vocals, and Greg Latty on drums), alongside a young, up-and-coming hip-hop group called The Fugees. I was in my early 20s, barely a year into learning the bass.

Greg was already Greg Tate—a force of brilliance, language, and cultural disruption, founding writer at The Village Voice and a founder of the Black Rock Coalition (BRC). Despite his stature, he never led with that. He made space. He saw people. And I was blessed to be one of those people.

After the gig, I approached Marque to ask him about the unusual, futuristic instrument he had been playing. That was the last moment I remember feeling like a stranger. I had the fortune to just be walking by that day—but it would be a moment that would dramatically change the trajectory of my life. In a heartbeat, I was officially enrolled, adopted, and absorbed. The BRC became my music school and its founding members my new family. The BRC was a radical home for those who played outside the lines. They were a community of world‑class musicians who loved to rock, groove, shred, and bend genres when the industry told them there was no room. It was Black, diasporic, loud, free, and very pro-woman.

For a Filipina-American girl shaped by hip-hop, alternative rock, and rebel music, coming up in a music industry where literally no one playing a bass looked like me, it gave me the permission I desperately needed. Today, I am deeply aware and profoundly honored that this foundation shaped the worldview I carry with me to this day.

The BRC manifesto, written by Tate, lit a fire under me:

“The BRC rejects the demand for Black artists to tailor their music to fit into the creative straitjackets the industry has designed. We are individuals and will accept no less than full respect for our right to be conceptually independent.”

Those words cracked me open and held me together at the same time.

Just a few years later, when Greg and I were living blocks apart on Edgecombe Avenue in Sugar Hill, Harlem, NYC, we’d grab lunch at our local Oaxacan joint. Over enchiladas suizas, we joked and talked while Greg made every meal feel like a masterclass.

At one of those lunches, he invited me to join a new band he was putting together: Moomtez with Alice Smith and Justice X on vocals, Latasha Natasha Diggs spitting spoken word, Greg and Rene Akan on Guitar, Trevor Holder on drums, and me on bass. That band was yet another Tate eruption of sound and freedom. He wrote songs and gave me the grooviest bass lines that felt so natural for me to play, as if I’d written them myself.

But my fondest memories with Tate weren’t in the spotlight. During those years on Sugar Hill, we were part of an unruly yet loving family tribe, sharing the best of life’s milestones...like driving down to the Gullah Geechee Islands to bear witness as Greg jumped the broom under an ancient cluster of low-country oak trees.

When I was majoring in writing at The New School in Greenwich Village, having access to Greg was like having my own personal literary sensei with rhythm and rhyme in his counsel. After reading one of my pieces, Greg looked at me and said, “The vibe and the content are there, but you need to learn The Power of the P.” I blinked. “The what?”

“The Power of the Period,” he said, deadpan. It was Greg’s loving assassination of my run-on sentences! (Peeking through the ether: Have I learned it yet, Greg?) LOL.

Over the years, Greg would occasionally laugh and bring up a certain systematic takedown I had engineered during an epic game of Monopoly on Sugar Hill. The players that night? Tamar-Kali, Freedome Bradley-Ballentine, Sharrif Simmons, and jessica Care moore. We were wheeling and dealing, trading properties with lyrical jabs, making and breaking alliances like it was a cipher. Greg sat off to the side, noodling on an acoustic guitar, equal parts amused and bemused. He was far too evolved—too cosmically inclined—for something as capitalistic and cutthroat as Monopoly. “Max,“ he said, marveling at my prowess, “you play like a benevolent oligarch with a grudge.“ He never let me live it down!

Greg had his own special way of encouraging. He’d call me “Max the Mule.” I’d laugh every time, but I knew it was his way of paying a high compliment. Tate-speak for: you get shit done, no matter what the terrain, no matter the weight of the burden. Then, with a twinkle in his eye, he’d tack on: “Black don’t crack, but Flip don’t slip.” It was classic Greg. Part praise, part punchline.

After I moved to the West Coast, our ritual shifted. Senegalese lunches. Whenever I was back in New York, we carved out time for thieboudienne, ginger juice, and bissap. By then, we carried enough life behind us to reminisce, to lean into the love, the nostalgia. These were sacred salons.

Our last lunch together is the one that lingers most in my memory. Sitting across from each other, I asked: “Tate, you’ve built your life masterfully talking about everyone else...but when are you going to tell your story?”

He nodded. “Yeah. It’s time,” flashing that understated, mischievous Tate grin. “And everybody alive to tell the story with me still got their swag.” We planned to make a doc about the Black Rock Coalition, but then, just a few months later, he was gone.

Devastated. Gutted. In mourning. I carried the sharp regret of never getting Greg on camera to tell his own story. But when he left us, the community of artists and intellectuals lit up ablaze in our grief. We gathered, we spoke, we remembered, sharing our infinite stories of Tate. And in that chorus of memory, it became undeniable: it was our turn to canonize the canonizer.

Now, I’m in production on a documentary film called Talk About Tate—because his story needs to be told. Greg always made time for his community, for artists, for the young ones who didn’t yet know they were geniuses. With his words, he documented his culture, and with his presence, he built his community.

And now, it’s the culture’s turn to remember. Those of us who were shaped by him must speak, sing, and play his name into permanence. We’re here to tell Greg’s story from the inside out. It’s our turn to Talk about Tate.

Why Greg Tate Day?

Greg Tate Day — October 19th — is an important way to honor his story, his singular mind, his resonant voice. On that day, I’ll be plucking my axe in public for the first time in a decade on the streets of Harlem, playing with a musical ensemble of Tate’s creation, Burnt Sugar Arkestra Chamber — legendary guitarist Vernon Reid will conduct.

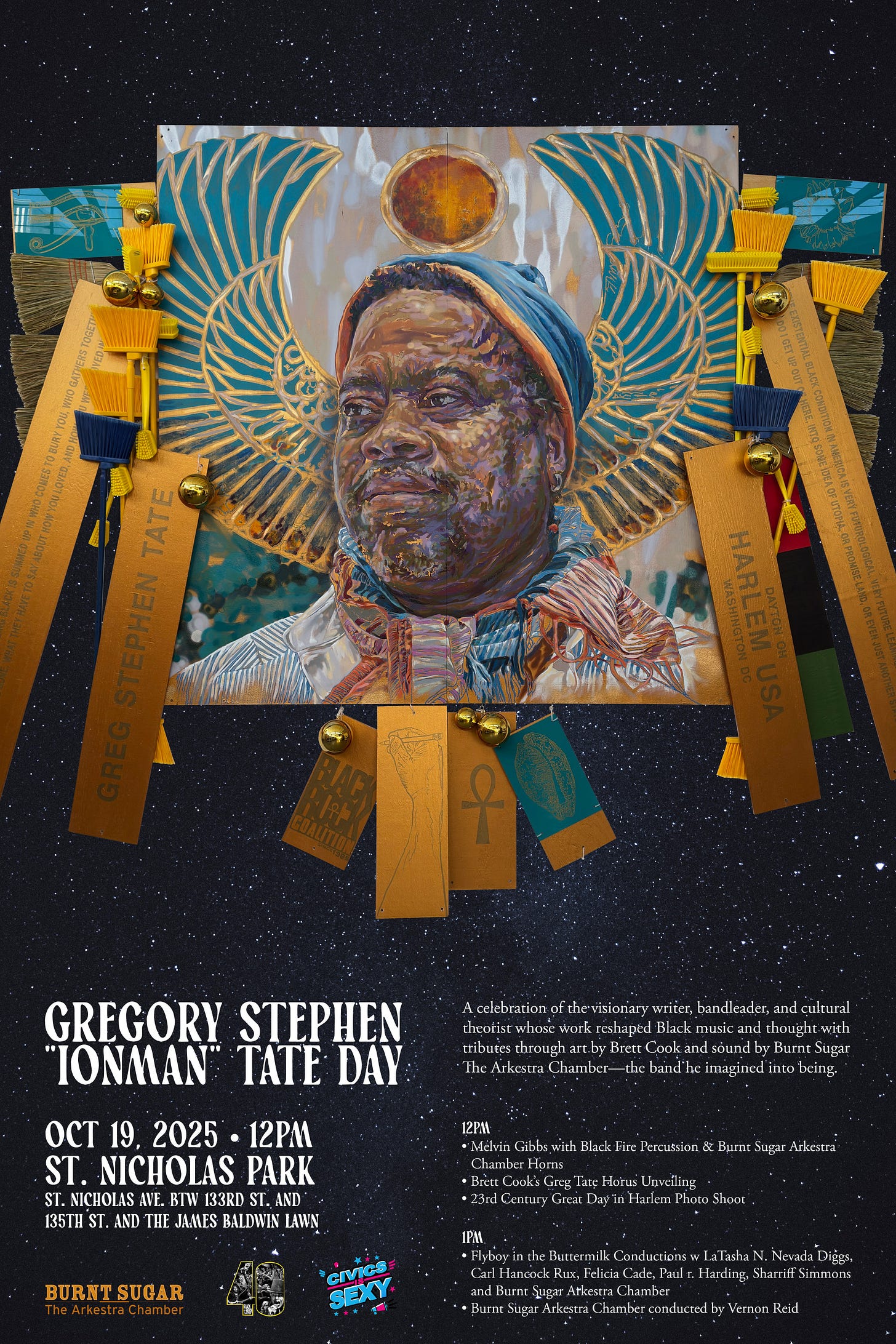

The anchor for the inaugural Greg Tate Day will be a new public artwork by internationally acclaimed artist Brett Cook. A 1997–98 Studio Museum in Harlem Artist-in-Residence alumnus, Cook is creating an imaginative portrait of Greg Tate inspired by his own decades-long practice of making “cultural artifacts” of love and care in and with communities.

Cook’s connection to Harlem runs deep. His seminal 1990s project Expressions of Harlem installed seven large-scale portraits with quotes from neighborhood residents across public sites. For Greg Tate Day, Cook returns to this lineage with Greg Tate Horus in Harlem, a temporary public installation at 134th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue approved by NYC Parks’ Temporary Art Program. A community procession and Burnt Sugar offering is planned for October 19th. Cook’s portrait doesn’t just honor Tate’s image; it places his spirit back into the streets he loved, echoing his legacy into the future.

What Greg wanted more than anything was for his people to waste nothing—not one drop of their talent. He felt the urgency, the mandate, for voices of free expression to put their work into the cultural record. He summoned us to take our shit off the shelf and let it shine. By honoring him, we radiate and honor the best in ourselves. As my brother Freedome puts it:

“Tate spoke about how art can change society, and artists as civic provocateurs. I know Greg is with us and pulling the strings from parts unknown.“

Because that’s the thing. Greg was civics. Not the dry, procedural kind—but the deep, lived spirit kind. The kind that reimagines what it means to be in public, to hold power, to remix reality. Tate reminded us that artists shape society. That we are not marginal—we’re foundational.

So yes—let us canonize the canonizer.

Name the day. Raise the volume. Feed the block. Teach the babies. And let the “furthermucker” fly. Because Greg Tate made space for all of us to be more than what they told us we could be.

And if that’s not civic power, I don’t know what is.

Greg Tate Day isn’t just a remembrance; It’s a call to enshrine his cultural brilliance in public memory. It’s a reminder that civic life doesn’t just live in voting booths or courtrooms. It pulses through art, poetry, music, and that guitar solo that makes you weep and rage at the same time.

There was never anyone like Greg Tate—and there never will be. Tate didn’t just write about culture. He shaped it. Through his signature syntax, cutting analysis, genre-bending artistry, and radical tenderness, he created a wholly new way of seeing, sounding, and saying. To be in conversation with Greg Tate was to be pulled into orbit intellectually, musically, spiritually. And for those of us lucky enough to be raised in the world he helped create, his legacy is not abstract. It’s personal.